ACDC Audio

The Vacuum Tube History

Introduction

Its invention enabled a leap forward for the wireless technology. Many new and exciting applications were found for these new devices. Vacuum tubes were used first as telephone repeater amplifiers and then in many others applications, not always linked to communications. Electronics was born. Actually the history of the vacuum tube might be seen as the first chapters of the history of electronics.

Today, vacuum tubes (or thermionic valves) are rarely seen, only appearing in vintage radio equipment. Even the few areas where vacuum tubes were previously found are now overtaken by semiconductor technology. The only field where tubes are still unmatched is the high frequency high power amplification. That is above 50 MHz, when power involved is in excess of 10 KW. Most obvious applications of this kind are Broadcast Amplifiers (see here an example), Radars, and Particles Accelerators Drivers (for example in a Rhodotron).

How it started

The first vacuum tube was not made until the beginning of the 20th Century. Nonetheless there were hints of its future discovery many years before. Professor Guthrie made one of the first discoveries leading to the thermionic valve in 1873. He was investigating effects associated with charged objects. He noticed that a red-hot iron sphere negatively charged would discharge itself. He also found out that this did not happen if the sphere was positively charged.

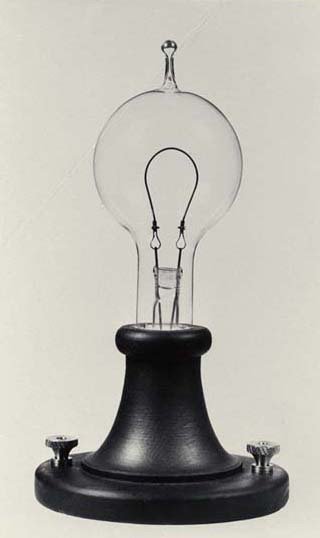

In 1883, the American inventor Thomas Edison made the next important observation. Edison was working on electric light systems. One of the major problems he was facing was their short life. The filament life was a problem, but the main limiting factor was that the bulbs quickly became blackened. At first it was thought that it was caused by atoms of carbon from the filament hitting the glass. As it was known that the particles leaving the filament were negatively charged, he tried to prevent those particles hitting the glass. The most successful method that Edison tried was to place a metallic element into the envelope. He reasoned that if this second electrode was made positive, particles would be attracted away from hitting the glass of the bulb. Experimenting with the polarity of the charge on the second electrode, Edison saw that when the second element was made positive with respect to the filament then a current flowed in the circuit. On the contrary, this did not happen when the potentials were reversed. Edison patented what he found, but he did not understand the underlying physics, nor did he have an inkling of the potential value of the discovery. Even so it became known as the Edison Effect. The seed had been sown for later discoveries.

Developments

The history of the vacuum tube continues with the work of a prolific scientist: John Ambrose Fleming. Like Edison, Fleming was also fascinated by the effect and started to perform experiments around the idea. For example in 1889 he had some bulbs made up for him by the Ediswan Company in UK. Using those bulbs he reproduced the Edison Effect, using a steady state charge.

A few years later he had the idea to use alternating potentials within this setup. He observed that if an alternating current with a frequency between 80 and 100 Hz was passed through the bulb, then only one half of the cycle was passed. In other words it was rectified to produce a direct current. In those times there was a lack of understanding about the operation of the device. Therefore no further progress was made.

In 1897, Sir Joseph Thomson discovered that atoms were made from even smaller particles, one of which was negatively charged: the electron. Accordingly it was quickly realized that it was electrons that were being emitted from the heated filament in the bulb. This also explained why they were attracted to an electrode with a positive charge.

A great chapter of the history of the vacuum tube: Fleming’s valve

In addition to his work at University College London, Fleming was also a consultant to Marconi. Marconi was at this time rapidly increasing the distances over which wireless signals could be used for communication. For example, in 1901 he made the first transatlantic transmission. Seeking to improve the quality and distances in wireless communications, Fleming saw that the major limitation was the sensitivity of the receiving equipment. This was caused by the poor sensitivity of the detector. At this time magnetic detectors were used, and those were very inefficient.

Fleming was searching ways of improving this, and in November 1904 whilst he was walking along Gower Street in the West End of London, he had what he called « sudden very happy thought ». He wondered if the Edison Effect could be used to rectify what he called the « feeble to and fro motions of electricity from an aerial wire ». Fleming set up an experiment and was able to prove that his idea worked.

Concept of the diode vacuum tube

Fleming called his new invention an « oscillation valve » because it acted in a similar way to a valve in a pump that allows gas or water to move in only one direction. He patented the idea that was clearly a major step forwards in wireless technology. Even though the vacuum tube was still in its infancy it was a major improvement over the coherer or magnetic detectors that were available at the time.

Despite its clear advantage over other detectors, Fleming’s oscillation valve or vacuum tube was not widely used. Valves or tubes were difficult and expensive to make. Their heaters consumed large amounts of power and this had to be supplied by expensive batteries. Additionally some cheaper devices were discovered in 1906. Devices that were forerunners of the Cat’s Whisker detectors that were used in crystal sets until the mid-1920s appeared. Those devices had many limitations but they were very much cheaper than Fleming’s oscillation valve and as a result they were quickly adopted.

more history of the vacuum tube: the audion

To continue with the history of the vacuum tube, we’ll have to talk about the Audion.

Even though crystal detectors were very successful, several people continued to investigate wheter they could develop vacuum tube technology whilst avoiding any infringement of Fleming’s patent. It was De Forest, an American who had been working on a variety of areas associated with wireless, who made the next and crutial vacuum tube development. He had been researching Fleming’s diode valve. Having investigated the idea, he took out some patents for improvements in 1905 and 1906 where he introduced a third electrode. Then, in 1907, he took out a patent for a three-electrode device where the additional electrode was placed between the anode and cathode. This electrode had a fine grid structure. He called this device his Audion which he used as a leaky grid detector, not realizing its full potential.

It was not until 1911 that the vacuum tube was used as an amplifier. After this discovery people were quick to try to exploit it. De Forest built an amplifier using three Audions and demonstrated it to the telephone company A.T & T. Although the performance was poor they saw its potential and soon started to build repeaters using vacuum tubes which they had improved. Naturally as soon as the tube was used as an amplifier, people were quickly able to use it as an oscillator. Indeed, one of the problems encountered was difficulties in preventing oscillations. The cause of those oscillations was the high values of grid anode capacitance.

improvements

In these early days of vacuum tubes, their operation was not fully understood and there were a number of misconceptions. For example: it was thought that some gas molecules were needed in the envelope for it to operate correctly. These tubes were known as « soft » tubes. In 1915, an American scientist named Langmuir proved that gases were not required in the envelope, on the contrary. Soon after this discovery new highly evacuated tubes known as « hard » tubes were produced and these exhibited far better levels of performance.

More grids, more grids…

The early vacuum tubes exhibited very high levels of anode-grid capacitance. It was therefore very difficult to prevent the circuits that used them from bursting into oscillation. This was especially true when they were used at frequencies above a hundred kilohertz. Several attempts were made to overcome the problem.

One major milestone in the history of vacuum tubes was set by H. J. Round. In 1916 he produced a low capacitance valve known as the Type V24.

For this tube, Round had the idea of keeping the anode lead away from the grid by passing it out of the top of the glass envelope and not through the base at the bottom. Whilst this gave a significant improvement, it was not the complete answer.

The solution to the problem was discovered in 1926 by adding a further grid. Known as the tetrode this vacuum tube used a second grid called the « screen grid » between the first or « control grid » and the anode. Its introduction reduced the anode to control grid capacitance to almost zero and solved the problem of instability.

Then in 1929 the tetrode itself was improved by the introduction of another type of vacuum tube termed the pentode. This tube had a total of five electrodes, the additional one being a third grid called the suppressor grid. This overcame the problem encountered with the tetrode of a discontinuity in its characteristic caused by electrons bouncing off the anode.

Apart from making changes in the operation of valves by adding additional grids, further improvements were made in the heater arrangements. One of the main problems with early tubes was that the circuit configurations were limited because the heater and cathode were one and the same. It was discovered that the cathode could be indirectly heated. This meant that the heater could be electrically isolated from the cathode. The advantage was that the heater did not need to be run from a battery supplying DC. Instead an AC supply derived from the mains could be used.

vacuum tubes history: the rise

The introduction of the tetrode and pentode brought revolutionary improvements in performance. As a result the use of vacuum tubes rose dramatically. Thermionic valves were used in radios which by this time were very popular, but also found many other uses.

Of course the vacuum tubes history is intertwined with the history of television. The first television sets available to the public appeared in 1935. Many special tubes were developed for the sole television industry. By the late 1930s many thousands of different types of vacuum tube were being manufactured by a large number of different manufacturers appearing both in the USA and in Europe.

Many of the vacuum tubes introduced in this period have long since disappeared from common use. However there are a few which were very successful remaining in new designs for a long time. One such valve was the 6L6 used in many guitar amplifiers until quite recently. In many ways it was quite revolutionary because it was the first beam tetrode. It used a new technique to overcome the discontinuity in the characteristic of the tetrode caused by electrons bouncing off the anode. Rather than using a suppressor grid it used a new arrangement connected to the screen grid. This tube became so popular that it was later modified for RF applications by giving it a top cap for the anode. This vacuum tube was called the 807 and was widely used in transmitters in the Second World War and afterwards.

Prior to the war all tubes had used special metal or plastic bases attached to the glass envelope to hold the pins. After the war miniaturization and improvements in manufacturing techniques enabled the pins to be mounted into the glass envelope. By doing this much smaller tubes were made and costs were reduced.

history of the vacuum tubes: today

The reign of the thermionic valve did not last forever. Developments in semiconductors resulted in the invention of the transistor in 1948. This meant that smaller, reliable, and less power hungry devices could be made. The success of the transistor was far from instantaneous. It took until the 1960s before domestic radios used them widely. Even then many vacuum tube radios remained (and still remain) in service for many years afterwards. Like any other story, the history of the vacuum tubes will end one day. Today thermionic technology is still used but in limited areas. High power transmitters still use tubes, like the 4CX20000 able to deliver 35 KW in the FM broadcast band. But even in this field power MOS-FET’s are beginning to take market shares.

But to many people, transistors do not offer the same lively feeling as a tube does. They don’t have the warm friendly glow of a valve. To those who worked with tubes, there will never be anything that can equal them.

production

Since 1964 the famous tube factories like Mullard, Telefunken, RCA, Western Electric or Philips either closed or stopped production of most -if not all- valves. Only high power high frequency tubes were still manufactured. Around 1980 army forces around the world (especially the US Navy, US Army and most of the European armies) started to resell their spare parts of tubes equipments as those were not needed anymore. Hundreds of thousands of tubes, usually manufactured between 1935 and 1965, were made available for the public. Those valves are called New Old Style, NOS in short. New because they were never used, Old Style because those were manufactured long ago. Another steady source of tubes is factories located in the former USSR. Those are producing valves almost (if not totally) identical to those made in western countries between 1945 and 1960. Of course those manufacturers are now using modern technology and materials. Electro-Harmonix, SED and Genalex (Russia), Euro Audio Team (Czech Republic) and JJ Electronic (Slovak Republic) are among the best. The last source for tubes is China. There are dozens of Chineese factories, like Shuguang, manufacturing valves with a quality and reliability ranging from very poor to very good. The SINO brand is a vast improvement over what was available from China just a few years ago.

This ends this small serie of articles about the history of the vacuum tubes. We hope you have enjoyed the reading